First Ever Black Hole Image Released

Astronomers

have taken the first ever image of a black hole, which is located in a distant

galaxy.

It measures

40 billion km across - three million times the size of the Earth - and has been

described by scientists as "a monster".

The black

hole is 500 million trillion km away and was photographed by a network of eight

telescopes across the world.

Details have

been published today in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Prof Heino

Falcke, of Radboud University in the Netherlands, who proposed the experiment,

told BBC News that the black hole was found in a galaxy called M87.

"What

we see is larger than the size of our entire Solar System," he said.

"It has

a mass 6.5 billion times that of the Sun. And it is one of the heaviest black

holes that we think exists. It is an absolute monster, the heavyweight champion

of black holes in the Universe."

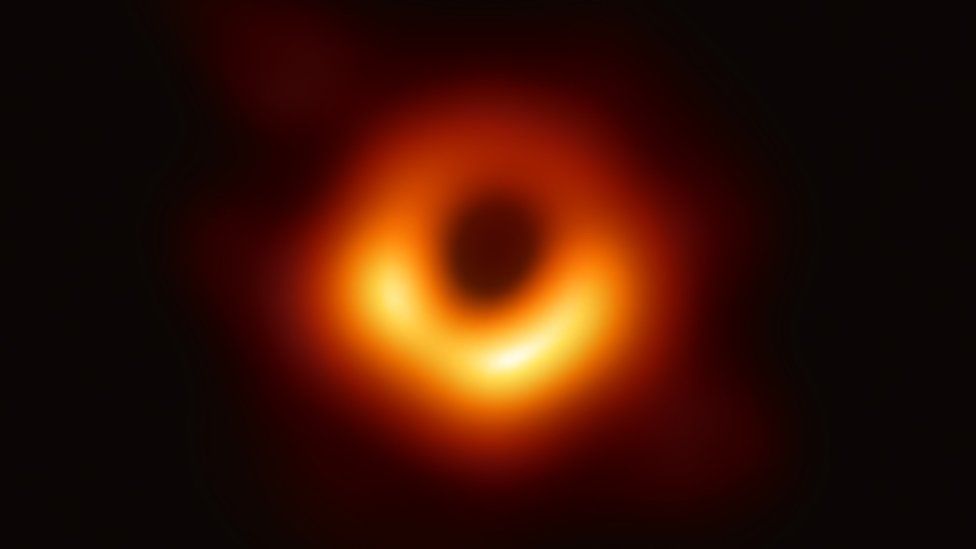

The image

shows an intensely bright "ring of fire", as Prof Falcke describes

it, surrounding a perfectly circular dark hole. The bright halo is caused by

superheated gas falling into the hole. The light is brighter than all the

billions of other stars in the galaxy combined - which is why it can be seen at

such distance from Earth.

The edge of

the dark circle at the centre is the point at which the gas enters the black

hole, which is an object that has such a large gravitational pull, not even

light can escape.

The image matches

what theoretical physicists and indeed, Hollywood directors, imagined black

holes would look like, according to Dr Ziri Younsi, of University College

London - who is part of the collaboration.

"Although

they are relatively simple objects, black holes raise some of the most complex

questions about the nature of space and time, and ultimately of our

existence," he said.

"It is

remarkable that the image we observe is so similar to that which we obtain from

our theoretical calculations. So far, it looks like Einstein is correct once

again."

But having

the first image will enable researchers to learn more about these mysterious

objects. They will be keen to look out for ways in which the black hole departs

from what's expected in physics. No-one really knows how the bright ring around

the hole is created. Even more intriguing is the question of what happens when

an object falls into a black hole.

A black hole

is a region of space from which nothing, not even light, can escape

Despite the

name, they are not empty but instead consist of a huge amount of matter packed

densely into a small area, giving it an immense gravitational pull

There is a

region of space beyond the black hole called the event horizon. This is a

"point of no return", beyond which it is impossible to escape the

gravitational effects of the black hole

Prof Falcke

had the idea for the project when he was a PhD student in 1993. At the time,

no-one thought it was possible. But he was the first to realise that a certain

type of radio emission would be generated close to and all around the black

hole, which would be powerful enough to be detected by telescopes on Earth.

He also

recalled reading a scientific paper from 1973 that suggested that because of

their enormous gravity, black holes appear 2.5 times larger than they actually

are.

These two

previously unknown factors suddenly made the seemingly impossible, possible.

After arguing his case for 20 years, Prof Falcke persuaded the European

Research Council to fund the project. The National Science Foundation and

agencies in East Asia then joined in to bankroll the project to the tune of

more than £40m.

It is an

investment that has been vindicated with the publication of the image. Prof

Falcke told me that he felt that "it's mission accomplished".

He said:

"It has been a long journey, but this is what I wanted to see with my own

eyes. I wanted to know is this real?"

No single telescope

is powerful enough to image the black hole. So, in the biggest experiment of

its kind, Prof Sheperd Doeleman of the Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for

Astrophysics, led a project to set up a network of eight linked telescopes.

Together, they form the Event Horizon Telescope and can be thought of as a

planet-sized array of dishes.

Each is

located high up at a variety of exotic sites, including on volcanoes in Hawaii

and Mexico, mountains in Arizona and the Spanish Sierra Nevada, in the Atacama

Desert of Chile, and in Antarctica.

A team of

200 scientists pointed the networked telescopes towards M87 and scanned its

heart over a period of 10 days.

The

information they gathered was too much to be sent across the internet. Instead,

the data was stored on hundreds of hard drives that were flown to a central

processing centres in Boston, US, and Bonn, Germany, to assemble the

information. Prof Doeleman described the achievement as "an extraordinary

scientific feat".

"We

have achieved something presumed to be impossible just a generation ago,"

he said.

"Breakthroughs

in technology, connections between the world's best radio observatories, and

innovative algorithms all came together to open an entirely new window on black

holes."

The team is

also imaging the supermassive black hole at the centre of our own galaxy, the

Milky Way.

Odd though

it may sound, that is harder than getting an image from a distant galaxy 55

million light-years away. This is because, for some unknown reason, the

"ring of fire" around the black hole at the heart of the Milky Way is

smaller and dimmer.

FROM .bbc.com/news/science-environment-

No comments