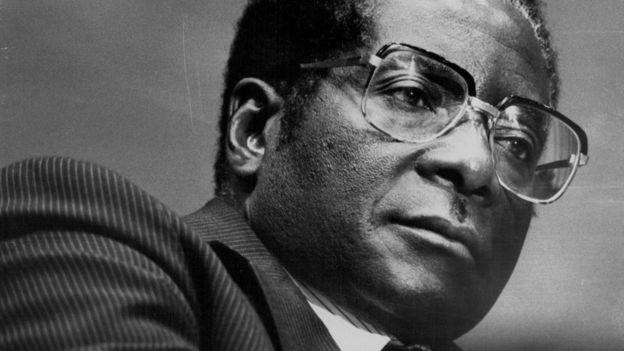

Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe's Ex-President, Dies Aged 95

Robert

Mugabe, the Zimbabwean independence icon turned authoritarian leader, has died

aged 95.

Mr Mugabe

had been receiving treatment in a hospital in Singapore since April. He was

ousted in a military coup in 2017 after 37 years in power.

The former

president was praised for broadening access to health and education for the

black majority.

But later

years were marked by violent repression of his political opponents and

Zimbabwe's economic ruin.

His

successor, Emmerson Mnangagwa, expressed his "utmost sadness",

calling Mr Mugabe "an icon of liberation".

Mr Mnangagwa

had been Mr Mugabe's deputy before replacing him.

Singapore's

foreign ministry said it was working with the Zimbabwean embassy there to have

Mr Mugabe's body flown back to his home country.

He was born

on 21 February 1924 in what was then Rhodesia - a British colony, run by its

white minority.

After

criticising the government of Rhodesia in 1964 he was imprisoned for more than

a decade without trial.

In 1973,

while still in prison, he was chosen as president of the Zimbabwe African

National Union (Zanu), of which he was a founding member. Once released, he

headed to Mozambique, from where he directed guerrilla raids into Rhodesia but

he was also seen as a skilled negotiator.

Political

agreements to end the crisis resulted in the new independent Republic of

Zimbabwe.

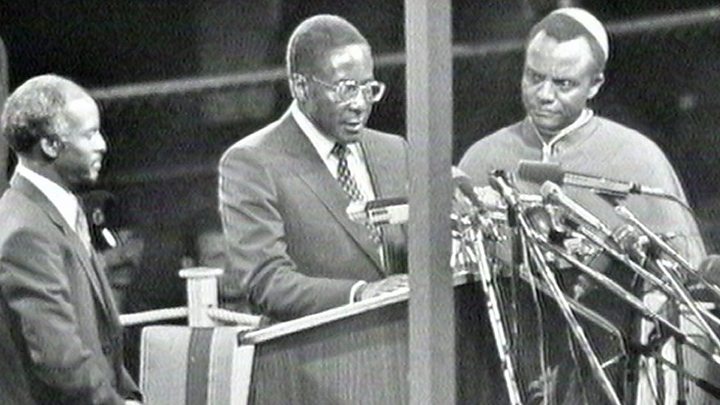

With his

high profile in the independence movement, Mr Mugabe secured an overwhelming

victory in the republic's first election in 1980.

But over his

decades in power, international perceptions soured. Mr Mugabe assumed the

reputation of a "strongman" leader - all-powerful, ruling by threats

and violence but with a strong base of support. An increasing number of critics

labelled him a dictator.

He died far

from home, bitter, lonely, and humiliated - an epic life, with the shabbiest of

endings.

Robert

Mugabe embodied Africa's struggle against colonialism - in all its fury and its

failings.

He was a

courageous politician, imprisoned for daring to defy white-minority rule.

The country

he finally led to independence was one of the continent's most promising, and

for years Zimbabwe more or less flourished. But when the economy faltered, Mr

Mugabe lost his nerve. He implemented a catastrophic land reform programme.

Zimbabwe quickly slid into hyperinflation, isolation, and political chaos.

The security

forces kept Mr Mugabe and his party, Zanu-PF, in power - mostly through terror.

But eventually even the army turned against him, and pushed him out.

Few nations

have ever been so bound, so shackled, to one man. For decades, Mugabe was

Zimbabwe: a ruthless, bitter, sometimes charming man - who helped ruin the land

he loved.

In 2000, he

seized land from white owners, and in 2008, used violent militias to silence

his political opponents during an election.

He famously

declared that only God could remove him from office.

He was

forced into sharing power in 2009 amid economic collapse, installing rival

Morgan Tsvangirai as prime minister.

But in 2017,

amid concerns that he was grooming his wife Grace as his successor, the army -

his long-time ally - turned against the president and forced him to step down.

Deputy

Information Minister Energy Mutodi, of Mr Mugabe's Zanu-PF party, told the BBC

the party was "very much saddened" by his death.

"He's a

man who believed himself, he's a man who believed in what he did and he is a

man who was very assertive in whatever he said. This was a good man," he

said.

Not everyone

agreed, however.

George

Walden, one of the British negotiators at the Lancaster House Agreement in 1979

which ended white-minority rule, said Mr Mugabe was a "true monster".

The

agreement "turned out rather well... and looked good for a while",

but Mr Mugabe later became "a grossly corrupt, vicious dictator", he

said.

Zimbabwean

Senator David Coltart, once labelled "an enemy of the state" by Mr

Mugabe, said his legacy had been marred by his adherence to violence as a

political tool.

"He was

always committed to violence, going all the way back to the 1960s... he was no

Martin Luther King," he told the BBC World Service. "He never changed

in that regard."

But he

acknowledged that there was another side to Robert Mugabe, who had "had a

great passion for education... [and] mellowed in his later years".

"There's

a lot of affection towards him, because we must never forget that he was the

person primarily responsible for ending oppressive white minority rule,"

the senator said.

South

Africa's President Cyril Ramaphosa called Mr Mugabe a "champion of

Africa's cause against colonialism" who inspired our own struggle against

apartheid".

Kenya's

President Uhuru Kenyatta said Mr Mugabe had "played a major role in

shaping the interests of the African continent" and was "a man of

courage who was never afraid to fight for what he believed in even when it was

not popular".

Kenya will

fly all its flags at half-mast this weekend in honour of Mr Mugabe, he said.

Veronica

Madgen and her husband ran one of the largest farms in Zimbabwe before it was

invaded by Mr Mugabe's supporters, forcing the family to come to the UK.

Speaking to

the BBC, she recalled: "The tractors [were] being burnt, the motorcycles

[were] being burnt, stones [were being] thrown through the window… It was very

difficult to actually come to terms with what was happening.

"I was

sad for him and his family, because for the first 20 years he governed that

country, he was a good leader, until that threat of losing that election got

hold of him and he turned."

Yet Mr

Mugabe is likely to be remembered for his early achievements, the BBC's Shingai

Nyoka reports from the capital, Harare.

In his later

years, people called him all sorts of names, but now is probably the time when

Zimbabweans will think back to his 37 years in power, she says.

There's a

local saying that whoever dies becomes a hero, and we're likely to see that

now, our correspondent adds.

FROM .bbc.com/news/world-africa-

No comments